Getting older often means facing cancer, and now local researchers may understand why.

By Stephanie Soucheray

Cancer doesn’t care who you are, where you live or how much money you make. The disease can strike anyone at any time, and has thus become the great leveler of modern health.

But new research from the Triangle’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences is proving that some cancers do care how old you are, and that age, and the common genetic processes that follow, are a big disease risk.

NIEHS cancer researcher Jack Taylor said scientists have known for years that age is a leading risk factor for certain cancers. But now a new understanding of DNA shows why aging leads to cancer. This work is part of NIEHS’s broader examination of the environment’s impact on epigenitics and human health.

Taylor said the aging problem seems to come from a process called “methylation,” a modification that is usually associated with a reduced ability of DNA to be transcribed into RNA.

Research is showing that certain sites in the genome display overmethylation in seven types of cancer.

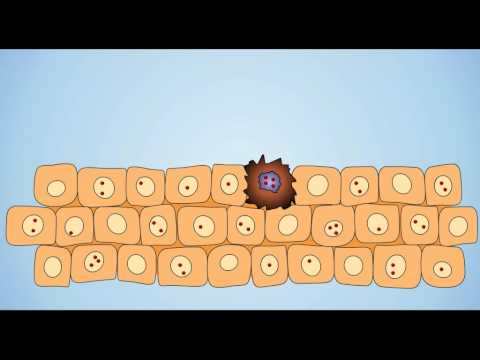

Overmethylation is akin to dust settling on a gene. Methylation does not alter the DNA, but it can cause it to fail to turn a cell on or off, thus making that cell vulnerable to cancer mutations.

Video courtesy National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

“The real surprise came when we looked at data about tumors and different types of cancer,” said Taylor, whose research was published online this month in the journal Carcinogenesis. Zongli Xu was the co-author on the study. “Seventy to 90 percent of the sites associated with age showed significant overmethylation in all seven cancer types.”

It’s known that aging affects methylation and known that methylation is frequently implicated in cancer, but this is the first study that looks at aging across the genome. Taylor said his work suggests that aging-related methylation may make it easier for certain cells to turn into cancer.

Taylor and Xu’s work is based on the Sister Study, which uses DNA from women who are currently healthy but have a sister with breast cancer.

Using blood samples, they looked at 27,000 separate methylation sites across the genome. They found that 30 percent, or 749, of the sites showed a significant methylation association with age. By the time a person is middle-aged, they may have 50 of these methylated sites, and each year they increase.

“We don’t know the answer as to why cancer hits some people instead of other people,” said Taylor. “It may be that diet and lifestyle may modulate methylation. And an environmental exposure might be good for you in one tissue but cause overmethylation in another.”

Taylor said this new understanding offers new pathways for cancer treatment. Most notably to Taylor, he hopes his work leads to interventions that can prevent overmethylation, and thus cancer from ever happening.

“My career is targeted towards prevention,” he said. “Exercise, drug exposure and lifestyle can affect the methylation.”

And because aging is a nearly universal experience, the next step for Taylor and his colleagues is understanding which early-life exposures influence methylation.

“In order for those things to show up as overmethylated in tumors, the theory is that the genes were overmethylated at the time the tumor began,” said Taylor. “That’s a big clue to understanding this disease.”